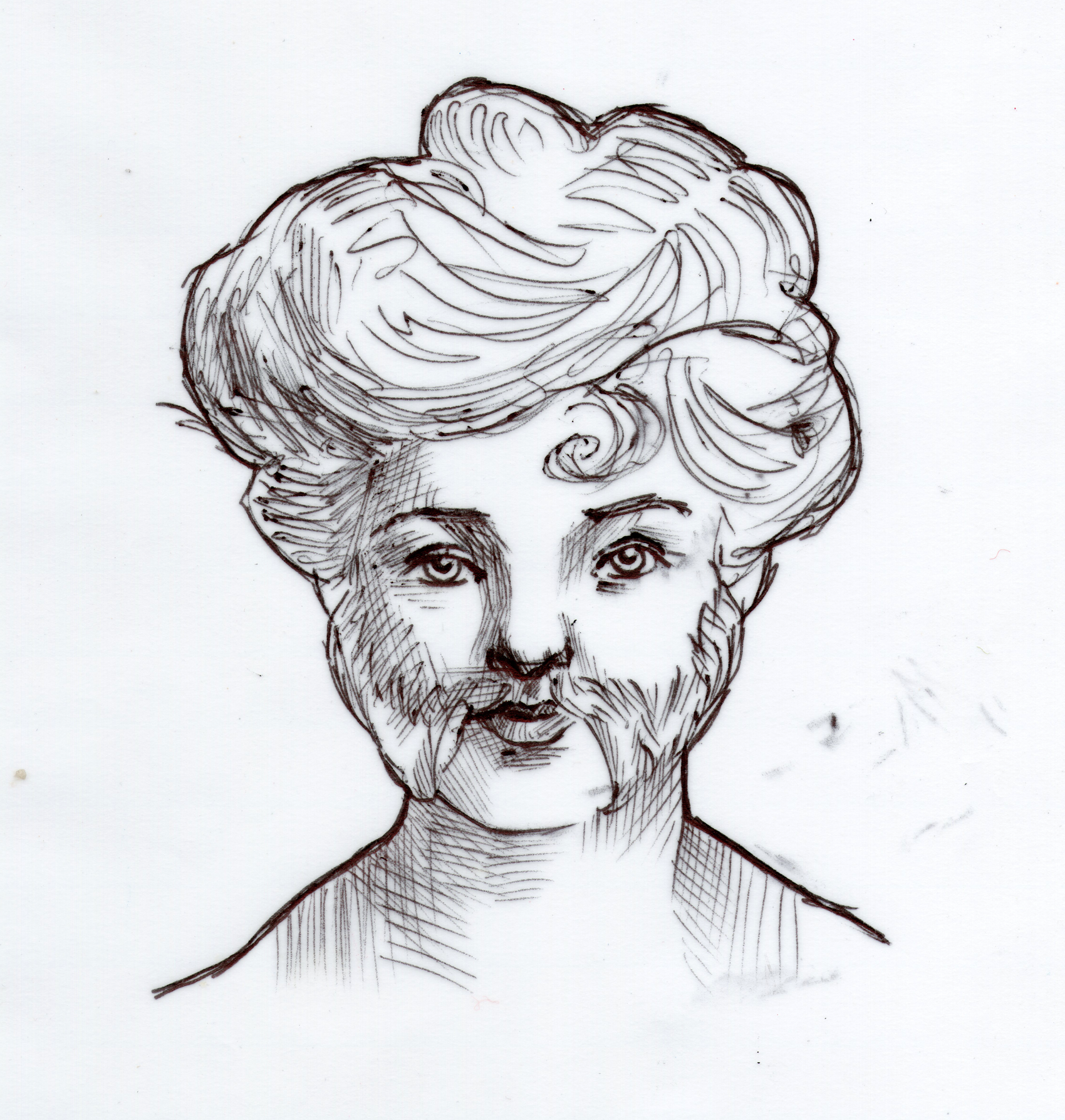

Dr Aloysius Doran, an Irish-born entomologist, was one of Britain’s foremost experts, both before and after the oxygenation event.

A beloved eccentric in his field, Dr Doran was born into one of Ireland’s most successful circus families, proprietors of Krinkle’s Wundergarden. His unusual private proclivities were the subject of much speculation in entomological circles. They reached the ears of the nation when ‘The Affair of the Butterfly Lover and the Bearded Lady‘ was reported, albeit under pseudonyms, in the cheap 1940s insect tabloid Legs.

“Born into one of Europe’s most prestigious circus families, the boy who would become Dr Aloysius Doran was fully expected to emerge into the high society of 1905 as the foremost purveyor of ‘Popped Corn & Attracktions.” Sadly, fate would intervene, in the sinuous shape of Edith Spurrell. He was the 16 year old heir to a circus empire, she was a 32 year old widow, and Europe’s most celebrated bearded lady.

“Edith, a timeless beauty in the mould of Sarah Bernhardt, but with a beard, first met the young Aloysius while she took the summer season with Krinkle’s Wundergarden. A young man could not help but be bewitched by those dark eyes, flashing above a glossy chestnut beard. Details are lost to time and delicacy, but what is known is that after an inseparable summer, Edith left for Vienna, never to return…

“Bereft, Aloysius tore through the caravan of tents and trailers, slamming doors when he could find them, flapping canvas when he couldn’t. Exhausted and weeping, he fell asleep in a corner of the elephant enclosure. What followed was a case of fleas so virulent, and impervious to dunking, shaving, and smothering, that the young Aloysius was sent to Oxford University for study.

“Surrounded by botanists and lepidopterists, as they tried to cure his infestation, Aloysius discovered that a correctly placed pin in the thorax of a moth was a balm to his aching heart. One month later, his fleas cured, his bites already scabbing, his father, the esteemed Dortmund Doran, arrived at Oxford to collect his son. The pock-marked youth begged for the chance to study at the venerable institution. Might he please devote his life to the bug, the louse, the fly? The wounds of his heart were too fresh – he could not bear to see the empty caravan of his beloved, her moustache comb lying discarded upon the floor.

“The shame to Dortmund was too great. He threw his whip, his billfold, and his lion-taming chair to the floor of the great hall, disinheriting his wayward son. The last the young Aloysius saw of his father was of a great scarlet back, striding across the quadrangle in the September sun.

“It was during this period, a time of golden academic pursuits, twinned with isolation from all he’d known and loved, that the young entomologist began to undertake frequent specimen-collecting expeditions. Sometimes in the company of other, giddier young undergraduates, but more often pursuing his solitary course, Aloysius would camp out, under the stars, moonlight twinkling on the specimen jars strewn about the grass.

“It was on one such occasion, travelling to categorise moth species in Sussex, that young man, drowsy with a secret sadness, and Alf Burnley’s best bitter, fell asleep while eating honey. He drifted pleasantly in memory, dreaming of the feather light touch of his lost beloved’s moustache…and awoke to discover that he’d been brought near the point of ecstasy itself by the tickling of myriad insectile legs on his honey smeared chest and arms. The young entomologist had discovered, had he but the words, that he was a hymneptrophile – one who attains sexual satisfaction through interaction with any of several forms of insect, as identified by Kinsey.

“This unusual propensity allowed Dr Doran to become pre-eminent in his field, feted by peers and superiors alike, but always with a secret loneliness in his heart. He would allow forelegs, mandibles, and the tap of pins through thoraxes to become the clockwork of the timepiece by which he measured the distance between him, and the woman he loved.

“And he would have been happy to immerse himself in his quiet academic river, winding his way to a peaceful legacy as a cataloguer of specimens, and nothing more. But the war, and the oxygenation event were to thrust him into prominence in a way he never could have expected –

The previous extract, from Dr Aloysius Doran’s biography, Tickled – The Private Life of a Lepidoptrophile. Penned by Dr Doran’s assistant Bertie de Sont-Saint-Sont-Clair, the book detailed Dr Doran’s early life in such a lurid fashion that many of Dr Doran’s colleagues distanced themselves from its publication. Privately, however, many claimed that the work was heavily censored by the biographer, and that Dr Doran’s proclivities had also led to a fashion of clean shaves among the other Oxford dons, for fear of Dr Doran’s wandering moustache comb.

His unusual tastes notwithstanding, Dr Doran also distinguished himself during the war as one of the firewatchers of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, pacing vigilantly on the roof, night after night. He also worked tirelessly to catagorise some of the new, enlarged insects, beetles and bugs emerging at the period. His intimate knowledge of the habits of invertebrates assisted many of the wartime engineers in shoring up bombed-out and abandoned buildings against the ravages of numerous enlarged species. His field guides also proved invaluable to MInsAg research teams across the world